The Torch Magazine, The Journal and Magazine of the

International Association of Torch Clubs

For 95 Years

A Peer-Reviewed

Quality Controlled

Publication

ISSN Print 0040-9440

ISSN Online 2330-9261

Volume 93, Issue 3

|

Finding

Common Ground:

Means, Ends, and Core Values in America Today by

Donald G. Hanway

As Americans

we say that our life together is

grounded in the rule of law. I

would argue that there is something

more foundational than our history or

our laws: our common values and how we

talk about them.

If you suspect that the religion of nihilism is newly regnant among many Americans—that is, the supposition that there is no underlying foundation for truth or values, because life has no ultimate purpose—you have some company. There is a good discussion of the nihilist phenomenon and the role it may be playing in our contemporary political culture in Garret Keizer's article entitled "Nihilist Nation" in the November 2018 issue of The New Republic magazine. I imagine, though, that very few readers of The Torch are part of that phenomenon. For the purpose of my paper, I'm assuming that America was founded on some shared values, and that many of these are still shared by the majority of us. *

* *

I submit that the following are some

primary American values, not

necessarily in this order:

First, a sense of fair play and equal opportunity, facilitated by access to quality education, and income sufficient for living. Second, public safety, so that one, regardless of the color of one's skin, may go to work, or to school, or to a concert or movie, without the fear of being attacked, and so that one may travel without fear of harassment or being put at undue hazard. Third, the right to some privacy, so that we can make some choices without scrutiny or interference (such as being able to cast a ballot in anonymity, or to dress minimally in our homes, or to conduct our sexual lives as we please, so long as we are not harming others). Fourth, community, so that we may benefit from interaction and shared resources, not only in business, but in the arts and in our religious life, and so that the less fortunate, including refugees, may be provided with many of the blessings we enjoy. Fifth, and many would put this first, freedom—not to do entirely as we please, where others are adversely affected, but to develop our interests and talents, so that all may benefit, and to choose those who will lead us. And here is one more value which must become central for Americans, even though it is currently only taken seriously by a relative minority, and that is the protection of life on this planet for future generations, including access to clean air and fresh water, sustainable agriculture, and responsible management of the oceans, as well as plant and animal life. Without the adoption of this value, the future of human beings on this planet is in jeopardy in the imminent future. Contrary to what some people believe, nature cannot save itself without human cooperation. *

* *

Just as

important as our values are the ways

in which he act upon them. Here too we

need some shared assumptions, some

ground rules.

In the summer of 1961, I took two courses at the University of Nebraska, prior to my entering as a full-time student in the fall. One was Trigonometry, which has been of use to me primarily in solving crossword puzzles; "cosine" is a word I rarely encounter elsewhere. The other was an introductory course in Ethics, in the Department of Philosophy. That course has become part of the bedrock of my thinking, about how humans relate to one another, both in private, person-to-person contexts and in large, public ones. The key ethical issue, I came to see, has to do with how we relate means and ends. That relationship continued to be important to me as I entered, several years later, into the study of theology and the Christian Church. Here is the crux of the issue: Can achieving a worthy end justify the use of unworthy means? Dr. Martin Luther King was among those who would answer, "no." In his Christmas Eve sermon in 1967, at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, King said: There have always been those who argued that the end justifies the means, that the means really aren't important. But we will never have peace in the world until men everywhere recognize that ends are not cut off from means, because the means represent the ideal in the making, and the end in process, and ultimately you can't reach good ends through evil means, because the means represent the seed and the end represents the tree. (King)He makes an excellent point, certainly. Still, as we gain life experience, we learn that the answer is not always clear-cut. As an example, was the use of nuclear weapons to bring a swift end to World War II justified, in preference to prolonged ground assaults? We can still debate that one. As I entered into my life's work as an Episcopal priest and congregational leader, I faced the ethical question of directing how funds were to be raised to enable the congregation's work. As I hardly need to tell you, there are a great many none-too-scrupulous ways of raising funds. Does achieving a worthy end, like the sustaining of a congregation and its mission, justify an unworthy means? I decided, no—our approach to stewardship, a Biblical mandate for church members, encompassing much more than the raising of funds, must be consistent with the Gospel, with the Good News we are called to proclaim: namely, that God's love is unconditional and in no way depends upon how much money, or time, or talent, one contributes to the work of the Church, or to society. Stewardship—that is, our management of all the gifts God has put into our hands—must be worthy of the end to be achieved, and to do that it must be based not upon guilt, or appeals to duty, or even upon the Church's need, but upon our thankful response to what God has given us. Stewardship, in other words, must be consistent with our worship and our preaching. Now, in our national discourse, we are faced again and again with the issue of ethics, and whether achieving a worthy end can justify the use of unworthy means. Involved with this question is the obligation to be truthful and honest. Will our language, in arguing for our causes, be understood as truth-bearing, or merely as instrumental? More baldly, may lying and misrepresentation be justified, as a means of securing the end we seek? Fact-checking has become increasingly necessary in recent years, as leaders in Congress and in the administration have used Orwellian twists of language to misrepresent what they are about, whether speaking of "reforming entitlements" such as health care assistance and Social Security, in order to shift the burden of taxes away from the more affluent, or to foster supposed greater efficiency in mail delivery by privatizing the U. S. Postal Service, after encumbering that organization with an extra burden of retirement funding. Journalists play an essential role in countering the tactics of disinformation, which prey upon fear and ignorance. The rise of social media platforms has provided a way, however, for narratives to be spread widely without fact-checking. Truth sometimes struggles to catch up. *

* *

Let's revisit

those six core values now and consider

the questions and debates that may

arise when we think about how ends

relate to means (keeping in mind that

we are focusing on ethics, as opposed

to policy, or who is winning and who

is losing).

Let's start with fair play and equal opportunity. Elizabeth Kolbert recently reviewed the contributions of Andrew Carnegie, railroad and steel magnate, who accumulated great wealth, and then addressed the concern of what to do with it. In an essay he wrote in 1889, which became known as "The Gospel of Wealth," Carnegie argued that giving great riches to one's children might be more injurious than helpful to them. Nor did he see giving alms to the poor as likely to guarantee any long-term improvement in their situation. Accordingly, he gave his wealth to institutions such as museums and universities and libraries. At the same time, Carnegie sometimes behaved like a stereotypical "robber baron." After breaking up a steelworkers union so that he could slash wages, Carnegie encountered the following media response: a cartoon was published in 1892 in the Utica Saturday Globe, showing two Carnegies joined at the hip: one holding a notice of pay cuts for workers, the other a smiling philanthropist brandishing a donation, establishing a library. We can be grateful for the good Andrew Carnegie did through his philanthropy. But here's the problem. Do we want a few rich people, who in many cases accrued their wealth by exploiting workers, to decide what institutions will be of greatest benefit to society? And does a good end—the accumulation of wealth, and giving much of it away—justify a bad means? Let's take the matter of public safety. Where and how will we have safe streets and schools? Will it be by armed citizen vigilantes? More incarceration? Or might it be through more investment in infrastructure, support for teachers, and more job opportunities for youth? Let's take the matter of privacy. In the September 2018 issue of Harpers, Harvard professor Katrina Forrester surveyed the history of privacy in America, drawing upon the work of Sarah Igo, noting our ambivalence about the role of government in securing our rights, while at the same time maintaining some control over who is allowed to invade our privacy and for what purpose. Should we let our privacy be compromised by our concern for public safety? What if someone's idea of their free exercise of religion impinges on someone else's idea of their privacy? Will women be forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term, on the basis of someone else's religious concerns? Let's take the value of community. Will we see our associations enriched, or diminished, by the arrival of newcomers with a different ethnicity or religious faith? Are we worried that a community whose faces are changing will imperil values we hold dear, such as stability and familiarity? Or will we come to understand that more diversity means more resources? The tactics of disinformation, as we have seen displayed on social media, frequently exploit our fears and our ignorance, when it comes to newcomers in our midst. We have also seen in recent years how much of the fear of others whose sexual orientation is outside the heterosexual norm has been reduced, as we have got to know them on a personal basis, and not as stereotypes. Young people have often led the way to our enlightenment in this matter. It is sad that religion has often been more of a stumbling block than a stepping stone in our getting to know and love our neighbors. Let's think about freedom, perhaps the most central and prized of our American values. We know that there is a difference between "freedom from" and "freedom for," the former being the removal of restraints or responsibilities as citizens, while the latter—"freedom for"—implies that we have a purpose and a value beyond lack of constraints upon our behavior. While much political rhetoric over the past forty years has portrayed government as an enemy, not a servant of the people, the fact is that government has served to provide more opportunity to more people, to ensure our public safety, and to enhance our prospects for community, through the establishment of regulations to restrain the unscrupulous, and taxation to provide for better infrastructure. The role of government has come to be seen by most of us as supporting the health of our nation, not simply defending us from outside attack. Those who would like for the role of government to be constricted are often favoring that for their own personal advantage, rather than, in the words of the Preamble to our nation's Constitution, "to promote the general welfare." In that light, let us probe a little more into our American value of freedom. Let us ask questions such as the following: "Whose freedom? Who benefits? And who pays the cost?" Will the safeguarding the environment for future generations (another of the core values I am exploring) require us to constrain the freedom of some (e.g., in disposing of hazardous waste) in order to protect the health of the many? Or, should employers be allowed to shortchange their employees in terms of benefits, simply for the sake of profit for owners and investors, while leaving the responsibility of providing some minimum health care to the rest of society? Asking questions about freedom – who is free, and who pays? – gets back to means and ends. Indeed, whichever value we examine, we find ourselves again facing that question. What is the goal to be achieved? Who will share in that goal? And what are the means to be employed? Who will benefit, and who will suffer? Costs and benefits need to be balanced against each other, whether we are talking about taxes, or regulations, national defense or environmental protections, personal privacy and freedom, or public safety. *

* *

I need to say

a little more about that value of

community. It's a value precious

to most of us, though perhaps not to

all. I heard recently about a

farmer in Nebraska who was laid up

with an illness, right at harvest

time. His neighbors got together

and pitched in, putting their own

harvesting on hold, while they got his

crops out of the field. That's

community in action.

My Dad, who grew up on a farm in western Nebraska, often told me of the surprising amount of community in those rural neighborhoods. People had to depend on one another and support one another in times of emergency and when times were tough. Do we have that same appreciation for the value of community today? At times we certainly do. In cases of disaster, such as floods and fires, we have seen countless examples of people stepping up to help people they don't even know. And we need to ponder this question: in a world that is so threatened by growing population and changing climate, do we not need community among nations more than ever before, at least as much as rural neighbors in Nebraska have needed each other? *

* *

Holding a

religious faith is not in itself one

of our shared national values, the

founders having decided, probably

wisely, that faith was a matter of

individual conscience. For many of us,

though, including myself, faith

grounds our values. In my faith

tradition, and some others, there are

two interdependent poles for worship

and for living: one is Word, the other

Sacrament.

Word is the expression of the values to which we subscribe, grounded in Holy Scripture, articulated in preaching and reflection upon our common experience. Word, centered in Scripture and the historic creeds of the Church, interprets and proclaims what we believe; Sacrament acts it out, first in the table fellowship of a common meal, and then in how we carry that understanding of community—loving your neighbor as yourself—out into the world, in our daily lives. Neither Word nor Sacrament stands alone. We need interpretation and proclamation, but we also need touch and action, whether it is feeding the hungry, or comforting the afflicted, and sharing from our bounty. One thing about which the Bible is very clear: we are to care for the outcasts and the immigrants – for we were once outsiders ourselves. How shall we promote and sustain our American values, which for many of us have deep religious roots and affinities? I would propose the following, as a modest beginning, as a way to promote and defend our values against their diminishment in much of our current social discourse. First, we can help to counter ignorance of the needs of others and of our planet, by fostering a reading culture. Let's start with the kids: read to them, and help them discover the adventure of reading. Second, we can counter fear by showing the benefits of community and diversity, starting by getting to know our neighbors—not just what they need, but what they have to offer. And third, we can counter deflection and the spouting of nonsense by supporting good journalism, honoring those who dig out the truth beyond "He said/She said," and who let us know what's really going on. Values, if they are to endure, need to be lifted up, made visible, not merely assumed. And they need to be lived, through all our commitments of time, talents, and our worldly means, so that all people, not only Americans, but all inhabitants of this fragile planet, may "live long and prosper." Works Cited

Forrester,

Katrina. "Known Unknowns." Review of The

Known Citizen: A History of Privacy in

Modern America, by Sarah Igo.

Harpers, Sept. 2018.

https://harpers.org/archive/2018/09/the-known-citizen-a-history-of-privacy- in-modern-america-sarah-igo-review/ Keizer, Garret. "Nihilist Nation: The Empty Core of the Trump Mystique." The New Republic, vol. 249, no. 11 (November 2018), 26-33. King, Martin Luther. "A Christmas Sermon on Peace." Beaconbroadside.com. https://www.beaconbroadside.com/broadside/ 2017/12/martin-luther-king-jrs-christmas-sermon-peace- still-prophetic-50-years-later.html Kolbert, Elizabeth. "Gospels of Giving for the New Gilded Age." New Yorker, August 27, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/ gospels-of-giving-for-the-new-gilded-age Author's

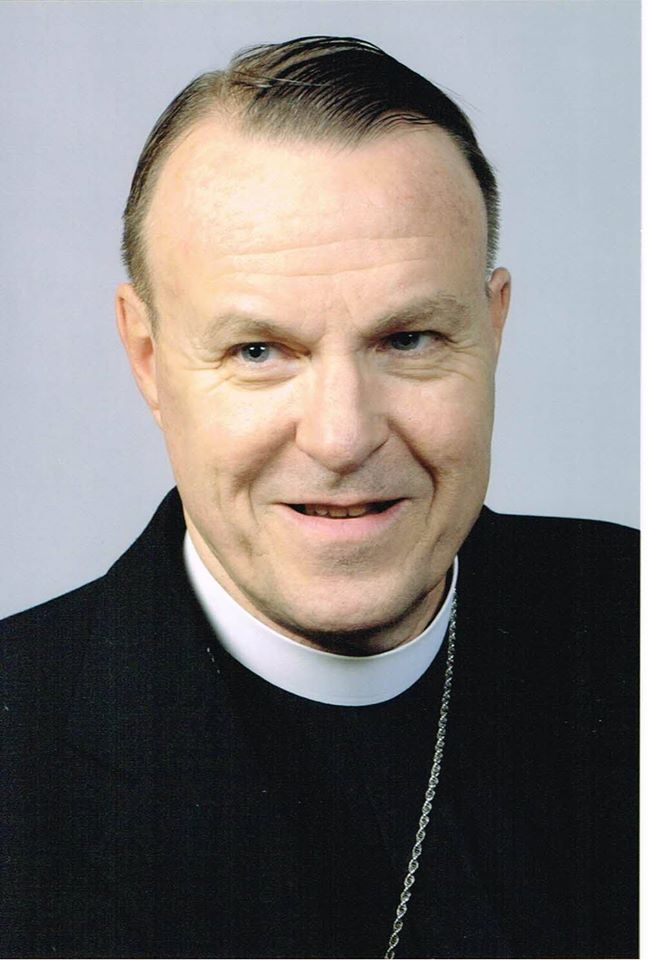

Biography

Donald G. Hanway has been

a member of the Tom Carroll Lincoln

Torch Club since 1993 and has

presented papers on such disparate

topics as movies, the phenomenon of

time, the writings of Ken Wilber, and

preparing for death.

A Phi Beta Kappa scholar at the University of Nebraska, Don was commissioned in the U.S. Army Signal Corps and entered on active duty upon completing his M.A. in Philosophy. He was awarded the Bronze Star for Meritorious Service in Vietnam. Ordained an Episcopal priest in 1971, Don served three churches in Michigan and Nebraska before being called back to serve the church where he began. He earned the Doctor of Ministry degree for advanced professional study from 1993 to 1997. Upon his retirement he wrote a primer for church people, sharing what he had learned about LGBTQ Christians. His book, A Theology of Gay and Lesbian Inclusion: Love Letters to the Church, was published by Haworth Pastoral Press in 2006. He is also the author of two novels and two collections of sermons. "Foundations of Our Life Together" was presented to the Tom Carroll Lincoln club on December 17, 2018. He can be reached at dghanway@gmail.com/ |