The Torch Magazine, The Journal and Magazine of the

International Association of Torch Clubs

For 94 Years

A Peer-Reviewed

Quality Controlled

Publication

ISSN Print 0040-9440

ISSN Online 2330-9261

Volume 92, Issue 3

|

Uncle

Sam's Con-Artists:

A Ghost Army of World War II by Barton C.

Shaw

In May 2013, PBS

broadcast a documentary about a World

War II military unit called the Ghost

Army. During the war few people knew

of the outfit's existence, and after

the conflict its operations remained

secret for several decades. Even

today, after almost all its records

have been declassified, most Americans

still know little about it.

At its most basic level, the purpose of the Ghost Army was to trick German commanders into drawing incorrect conclusions about what they were seeing and hearing on the battlefield. One of the Ghost Army's creators was Ralph Ingersoll, a captain working out of the Army's headquarters in London. At various times, he had served as the publisher of Fortune magazine, the managing editor of The New Yorker, and the founder of PM magazine. By all accounts he was opinionated and self-absorbed, with a real gift for lying. But he was also capable of original thought. His most unusual military proposal was to put battlefield deception in the hands of creative people such as painters, actors, stage designers, architects, photographers, and audio engineers.  Illustration 1: Four ghost soldiers, probably Camp Forest, Tennessee. The man on the right is Alvin Shaw, the author's father.

The Army approved

the plan on Christmas Eve, 1943, and

began scouring art schools for

recruits. Some self-taught artists—the

author's father, Alvin L. Shaw, was

one of them--were also selected. All

were sent to the 603rd Engineer

Camouflage Battalion Special at Fort

Meade, Maryland. Like other soldiers,

they got their share of guard duty and

twenty-mile hikes. Even so, the

artists found they were in a different

world with rules all its own. Their

telephones were probably tapped, and

from the beginning they were

constantly told to maintain silence

about what they were doing, that to

divulge anything might win them a trip

to a federal penitentiary.

Elsewhere, similar outfits were being organized. One specialized in extremely sophisticated radio transmissions, and another in battlefield sound effects. Finally, for security, a company of combat engineers was also preparing for secret duty. On January 20, 1944, these three units, plus the 603rd Camouflage Battalion, were united and became the "23rd Headquarters Special Troops." Ralph Ingersoll proudly dubbed the men of the new unit "my con artists" (Beyer and Sayles 15). Later they came to be called the "Ghost Army." What was afoot? In the case of the camouflage battalion, its men were taught how to build, inflate, and move rubber tanks (four men could easily lift a tank). They also learned how to camouflage a dummy tank—not so well that it could not be seen, and not so poorly that it would be suspicious. Other members of the Ghost Army perfected the use of large loudspeakers, which could be heard fifteen miles away. Their recordings broadcast the increasing or decreasing clatter of tanks and trucks on the move. Finally, other ghost soldiers were learning how to imitate the "fist"—that is, the different way each radio operator transmitted Morse code. This, for example, made it possible for an American unit to move out while a ghost operator gave the impression, by imitating the fists of the American unit's operators, that the unit was still in place. The Ghost Army received most of its training at Fort Meade, Maryland; at Camp Forest, Tennessee; and at Pine Camp, New York. During this period, my father's letters to my mother said nothing about what his outfit was actually up to. Instead he told her about firing a machine gun, of throwing live hand grenades, and of a tank running over his fox hole, while he was in it. *

* *

The Ghost Army,

1,100 men strong, departed for England

on May 2, 1944. Their ship convoy

evaded the U-boats and arrived in

Bristol on May 15. From there they

traveled to their encampment at Walton

Hall, a large manor house near

Stratford-upon-Avon. Some of the

ghosts took in Shakespearian plays;

others preferred the fleshpots of

nearby Leamington Spa.

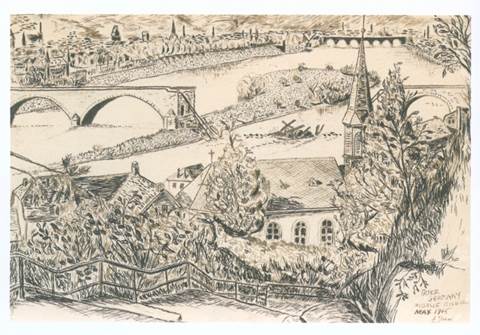

On the evening of June 6, my father was guarding the map room at Walton Hall. All through the night planes roared overhead. When he was relieved, he was told that the invasion of France had begun. When the rest of the ghost soldiers got the news, they all cheered. Then, slowly, they grew silent. By this point, there was a growing sense that theirs was a suicide mission. After all, what were they to do when the Germans trained their guns on the rubber tanks of the Ghost Army? The Ghost Army landed in Normandy about two-and-a-half weeks after D-Day. In early August, allied troops smashed through enemy defenses, and the German army fled across northern France with allied forces in pursuit. At Brest the Germans left behind a strong garrison, which was besieged by three American divisions. The Ghost Army was ordered to Brest, its mission to convince the Germans and French collaborators that another American division had arrived. The ghost soldiers employed the skills they had earlier mastered—the use of dummy tanks, fake radio transmissions, and deceptive sound effects. Shoulder patches were constantly changed, and a ghost soldier drove the countryside in a staff car posing as a major general. Ghosts visited cafes and talked within earshot of other patrons about the comings and goings of imaginary American units. When the German garrison finally surrendered, their general boasted that his army had done well considering that it had had to fight four American divisions. In fact, there were only three American divisions present, and the tiny Ghost Army. During the siege, U.S. forces suffered one serious breakdown in communication. A company of U.S. light tanks moved against a German position, expecting to be supported by a nearby company of heavy tanks. The supposed heavy tanks, however, were only ghost dummies, and the Germans destroyed the real U.S. tanks conducting the attack. The mistake was not the fault of the Ghost Army, but the incident nonetheless troubled many ghost soldiers. "It makes you feel lousy," one said decades later. If there was a silver lining in this, the incident may have taught the brass that the Ghost Army could deceive the Americans just as easily as it could the Germans. The Ghost Army now headed east trying to catch up with the advancing U.S. forces in northern France. Along the way, they chanced upon a warehouse filled with more than 6,000 bottles of cognac. Rather than allow this prize to fall into the hands of the enemy, they were forced to drink as much as they could. Some men remained sober, but many did not. It was said that the unit was out of commission for three days. On another occasion, one that ghost soldiers would never forget, two Frenchmen on bicycles inadvertently got past the guards and into the encampment. The French intruders were thunderstruck by what they witnessed: four G.I.s lifted and turned a forty-ton tank! A nearby soldier offered the Frenchmen an explanation: "The Americans are very strong" (Park 138-47). In all of this, one of the things that made the Ghost Army unusual was what its men did in their spare time: they sketched. Consequently, we have impressive water colors and pen and ink drawings of Fort Meade, the Atlantic crossing, Walton Hall, the Channel crossing, and Normandy. Some of the most moving were renderings of Trévières, a French town accidentally hit by US. Navy shelling.  Illustration 2. Sketch by Alvin Shaw of Trier, Germany, where the Ghost Army guarded a displaced persons camp. *

* *

By mid-September,

General George Patton's Third Army had

reached the Moselle River. He planned

an attack at Metz—but this would

briefly open a seventy-mile gap in his

line. The Ghost Army moved into the

opening, posing as the Sixth Armored

Division. The ruse worked, and after a

few days a real division—the

83rd—arrived. Afterward, the Ghost

Army was ordered to Luxembourg City.

There the ghosts lived in an old

Catholic seminary, earlier occupied by

the Germans. For the next few months,

the seminary became the center of

ghost operations. It was also the site

of a visit by Marlene Dietrich, one of

the most glamorous women in the world.

She sang a song for the troops that

she helped make famous, "Lili

Marleen."

The winter of 1944-1945 was said to be the coldest Europe had experienced in forty years. In mid-December, under the cover of a blizzard, the Germans launched their last great offensive—commonly called the "Battle of the Bulge." By chance the Ghost Army, returning from one of its operations, was at ground zero of the German assault. Four hours before the attack, the American command ordered the Ghost Army out. Most of unit withdrew to Verdun, the site of one of World War I's bloodiest battles. There they occupied dilapidated and miserably cold French barracks. Not far away were thousands of graves, where lay the victims of an earlier struggle. The Battle of the Bulge, which the Allies won, represented Germany's last hope on the western front. Even so, by 1945 the Rhine River had yet to be crossed. The Allied plan was to send in late March a large British force, supported by two U.S. divisions, across the Rhine in the Ruhr region. Ten miles to the south, the Ghost Army would impersonate another two U.S. divisions. This, it was hoped, would give the impression that the U.S. divisions, with the British force, had moved south for an attack. To be successful, the Ghost Army was required to do something it had never done before: it had to impersonate 30,000 men. Many of the old deceptions were employed. At the same time, German reconnaissance planes spotted the construction of large field hospitals, airports, and ammunition dumps. Hundreds of tanks seemed ready for a major assault. Of course, almost everything the Germans observed was fake. On March 29, British forces and two U.S. divisions crossed the Rhine with little resistance. The Germans had sent most of their troops south to fight the two imaginary divisions of the Ghost Army. This was the Ghost Army's most brilliant ploy. Some historians believe that the operation saved many British and American lives. The commander of the Ninth Army sent the unit a letter of commendation, and years later Tom Brokaw, the television news commentator, said that the mammoth deception was a "perfect example of a little-known, highly imaginative, and daring maneuver that helped open the way for the final drive to Germany" (Beyer and Sayles, jacket copy). The German army surrendered on May 7, 1945. The American military then used its ghost troops to guard five large displaced persons camps near Trier, Germany. Keeping control of camp DPs—especially the Poles and Russians—was difficult and sometimes dangerous work. "Everybody hated everybody," one soldier said (Kneece 264). Occasionally, inmates were murdered. My father took a Hitler youth knife from a man who was trying to sneak it into the camp.  Illustration 3: The Hitler Yough knife Alvin Shaw took from a man at DP Camp *

* *

By the end of September 1945, all

units of the Ghost Army had been

deactivated. Most ghost soldiers

returned to civilian life, some going

on to considerable distinction. Bill

Blass became a giant of the fashion

industry, Arthur Singer a brilliant

painter of birds. Ellsworth Kelly's

minimalist paintings are owned by many

of the world's great museums.

In the end, the Ghost Army engaged in twenty-one operations. The unit suffered three men killed and perhaps a dozen seriously wounded. Compared with the losses of most front-line outfits, these were slight casualties. The ghosts had been very lucky, and they knew it. The declassification of Ghost Army records has done much to bring the unit to the attention of historians. Four books have been written on the subject, and, as noted earlier, a PBS documentary has been aired. Brown University is collecting the work of Ghost Army artists. Finally, an effort is now underway in Congress to decorate the Ghost Army as it had previously decorated the Monuments Men—with the Congressional Gold Medal. Works

Cited and Consulted

Beyer, Rick, and Sayles, Elizabeth. The Ghost Army of World War II. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2015. Gawne, Jonathan. Ghosts of the ETO: American Tactical Deception Units in the European Theater 1944-1945. London: Greenhill Books, 2002. Gerard, Philip. Secret Soldiers: The Story of World War II's Heroic Army of Deception. New York: Dutton, 2002. The Ghost Army of World War II. Written, directed, and produced by Rick Beyer. Plate of Peas Productions. Public Broadcasting Service. 2013. Kneece, Jack. Ghost Army of World War II. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company, 2001. Park, Edwards. "A Phantom Division Played a Role in Germany's Defeat." Smithsonian, 16, no. 1 (April 1985): 138-47. Illustration 1: Four ghost soldiers, probably at Camp Forest, Tennessee. The man on the right is Alvin Author's

Biography

Barton C. Shaw, who

is now retired, earned his Ph.D. at

Emory University. He taught history at

Cedar Crest College, in Allentown, PA,

for over thirty years.

His book The Wool-Hat Boys: Georgia's Populist Party won the Organization of American Historian's Frederick Jackson Turner Award in 1985. In 2010, Shaw was winner of the Torch Club's Paxton Lectureship. Over the course of his career, Shaw has received other honors including a Ford Foundation Fellowship, a Fulbright Senior Lectureship at the University of Sheffield (UK), and a Cedar Crest College award for excellence in teaching. He is a member of the Lehigh Valley Torch Club, where he presented "Uncle Sam's Ghost Army" on February 1, 2018. He may be reached at < bcshaw@cedarcrest.edu>. ©2019

by the International Association of

Torch Clubs |