The Torch Magazine, The Journal and Magazine of the

International Association of Torch Clubs

For 94 Years

A Peer-Reviewed,

Quality Controlled,

Publication

ISSN Print 0040-9440

ISSN Online 2330-9261

Volume 92, Issue 2

|

God in

Experience

by Parker

English

A variety of

people have met what they think is God

in their own conscious experience,

their personal awareness. Some

of these people were understood by

themselves and by others to be

hallucinating, but others saw

themselves and were seen by others as

divinely inspired. For those who

believed themselves divinely inspired,

the God in their experience is

understood as independent of being

experienced—that is, He would exist

even if not experienced.

Indeed, He has caused and will

continue to cause various people to

have experiences of Himself. He

is real.

The following discussion is meant to show that such an experience alone, in and of itself, cannot be seen as adequate support for this view of God—not by anyone who thinks they have experienced God, nor by anyone who thinks various other people have done so. Our discussion begins with a summary of research by the distinguished anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann (2012) that seeks to "explain to nonbelievers" how certain Pentecostals "come to experience God as real" by virtue of speaking in specific prayerful ways. Luhrmann's explanation is clear and compelling. However, neither it nor those experiences prove their object is real in the sense of existing independently of the experiences in which it appears. The Pentecostal experiences do not prove this any more than do the ecstasies of those who think they experience God while influenced by psycho-active drugs such as LSD or psilocybin. Although neither type of experience proves God's independent existence, some philosophers think it remains possible that God does exist independently and appears in both types of experience. While appreciating this possibility, we argue that faith, in addition to any experience of God, is necessary for regarding Him as actually independent of that experience, as existing when not experienced. Experiences of

God Induced by Pentecostal Prayer

Luhrmann

participated both as a researcher and

as a congregant for two years apiece

in two Vineyard Christian Fellowship

churches; one in Chicago and one in

California. She describes the

roughly 600 members as ordinary,

decent, educated, smart. Most

were middle class, but some were

wealthy, and others were poor.

Most were white, but some were

minorities. All yearned

for "more" in life, especially

regarding love, peace, and

self-control. All yearned to

gain these things through faith in God

combined with prayers spoken to Him in

a three-part "technique."

In this technique, speakers first imagine God as "present" while delivering prayers of adoration, confession, thanksgiving, and supplication. According to Luhrmann, many adult Pentecostal speakers can imagine successfully in this way, often by behaving as children do with imaginary friends—for example, setting out a cup of coffee for God while drinking their own during morning prayer with Him. Second, speakers imagine they are not imagining; God as "internally" present in imagination is construed as "external" to it, as independent of it. Apparently, Pentecostals are sometimes able to take advantage of a "participatory theory of mind" in which, Luhrmann writes, they "recognize God's presence in what they had previously experienced as a fuzzy mental blur" (60), in "seeing, hearing, and touching above all" (161). At such moments, they treat these things as caused by God, develop a responsive prayer to Him; and then await further spontaneous and unexpected thoughts or sensations. Third, they "allow this sense of God […] to discipline their thoughts and emotions"; in particular, those who pray in this way sometimes feel that "God looks after them and loves them unconditionally" (xxi). Biblical prophets might be understood as having prayed with techniques similar to this. Luhrmann describes the technique as inherently ambiguous and only rarely successful in making God seem present in a speaker's conscious awareness. Prayers that did seem successful typically concerned another person for whom the prayer was delivered: "In practice, the prayers that really persuaded people of God's speaking to them in their minds were prayers for other people, in which the ordinary thoughts that floated into their mind during the prayer seemed uncannily appropriate for the person about whom they prayed" (49). Not just appropriate but sometimes effective: they changed "the listener's perspective from that of a scared human looking out at life's challenges to that of a creator God looking down with love" (115). In short, a sense of God as present was found from the "fuzzy mental blur" that inspired those of a Pentecostal speaker's prayers that themselves changed a listener's perspective from fear to comfort. Dan A'Ambrosio (2014) describes a confirming type of experience, the subject of this one being only the object of prayer, i.e., the person prayed for. Fuller Smith, a young baseball coach at the University of Mississippi, was at an away game with Donna Holdiness, who led the team's booster club. At the game, police told her that her husband had been struck and killed by a motorist while riding his bicycle. Smith told her she had to call her son. "I said, 'Fuller, I can't,' " Holdiness remembered. "He said, 'I will dial the number.' He handed me the phone and got down on his knees and started praying for the strength to tell my son his father was killed. It was the most amazing thing. I was calm, clear, and in control. I felt the arms of God almighty around me as that boy was on his knees praying strength for me." (44)

For Holdiness as well as for the

Pentecostals, speech inspired a person

to experience God. For

Holdiness, it was the one hearing the

speech. For Pentecostals, it was

the speaker; and perhaps a hearer as

well.

Experiences of

God Induced by

Changes in Brain Activity

There are two

especially good reasons why

speech-inspired experiences of God do

not prove his independent

existence.

First, Wilder Penfield (1958) and subsequent brain scientists have shown that direct electrical brain stimulation suffices to produce not just the fuzzy mental blurs associated with God's presence for Pentecostals but also visual and tactile images that cohere almost as well as do what is seen and what is felt of a normal object. In other words, the experiences of God as present during Pentecostal prayer might result simply because such prayer causes relevant changes in a person's brain activity, much as does meditation. But the changes in brain activity, not an independent God, might be solely responsible for those visual and tactile images (as skeptics assume also happens when God appears in deep meditation). The second reason concerns Walter Pahnke's (1966) double-blind Marsh Chapel experiment with psilocybin. Within an intensely religious atmosphere of music, readings, prayers, and personal meditation, almost all of the divinity students who ingested psilocybin reported an experience of God. This was not true of the students who ingested a placebo. Most of the psilocybin-affected students interviewed six months later reported "that the experience had […] motivated them to appreciate more deeply the meaning of their lives, to gain […] more tolerance, more real love, and more authenticity as a person by virtue of being more open and more one's true self with others […] need for service to others." R. R. Griffiths and his collaborators (2006) report similar results from a follow-up psilocybin experiment. In particular, the psilocybin-affected experiences they studied "had marked similarities to classic mystical experiences and which were rated by volunteers as having substantial personal meaning and spiritual significance," producing "sustained positive changes in attitudes and behavior that were consistent with changes rated by friends and family," including "[a]ltruistic/positive social effects." (1) In sum, psilocybin can produce experiences of God markedly similar to those classically associated with a view of God as real, as existing independently of experiences of Him. This said, we know that many objects of psilocybin-induced experiences in secular environments are not independent of those experiences—that is, that they are hallucinations. We can see for ourselves that a red fire hydrant does not really change color in an environment we share, that imaginary people do not really appear and interact with things we see and feel, and that time does not really speed up or slow down except at extreme velocities. Skeptics conclude that the God experienced by someone under the influence of psilocybin likewise does not exist independently of those experiences, but results from changes in brain activity caused by a psycho-active drug, ceasing to exist when not experienced. This result is relevant for understanding the God in experiences produced by Pentecostal prayer. In both cases, God-related experiences can be viewed as resulting for people who use one or another technique to alter the activity of their brains. For Pentecostals, it is prayer spoken with a specific technique; for the divinity students, it was ingesting psilocybin. Both types of experience can be viewed as resulting from unusual brain activity, as was true for the experiences that resulted from Penfield's direct electrical brain stimulations. If we assume that alterations of brain activities are responsible for the religious experiences, however, their objects should not be understood as existing independently of the experiences. (2) Rather, these objects should be viewed as ceasing to exist entirely when not existing as objects of experience. In Addition to

Experience, Faith Is Necessary for

Regarding the Supreme Being in any Religious Experience as Having Independent Existence

Prior to the

psilocybin experiments by Pahnke,

James B. Pratt (1941) had assumed, for

the sake of argument, that scientists

would eventually develop a completely

naturalistic explanation for

experiences of God. Scientists

would identify exactly which brain

activities yield these experiences,

and induce them with purely natural

methods—psycho-active drugs, for

example. As a result, Pratt

granted that experiences of God do not

prove His existence as independent of

such experiences. But Pratt then

observed that God might still be understood

this way. Specifically, He

might be understood as having created

humans so that His specifically

intervening grace would eventually not

be necessary for His appearing to us

in experience. Rather, He has

blessed us with the sort of bodies we

can manipulate so as to achieve that

experience without His

intervention.

The main problem with this otherwise intriguing possibility is that the objects of religious experiences in different cultures have incompatible features. Such an incompatibility implies that at least one of the objects in these manifestations of the divine cannot be real in the sense of existing independently of experience, existing when not experienced. This is interestingly true when the results of Judeo-Christian prayer are compared with those of traditional Ghanaian animists. Benjamin D. Sommer (2009) raised this type of point in explicating the distinction between monotheism and polytheism. Sommer explains the need for explication by observing that Judaism and Christianity are importantly like polytheism. Specifically, all posit the existence not just of the physical universe and the Supreme Being who created it but also of certain subordinate non-physical entities that help Him guide the universe. For Jews and Christians these are angels. For polytheists they are, among other things, deities and the life-forces of departed ancestors. Angels have relevantly less power than deities and life-forces, however. Sommer observes this is why only the Supreme Being for Jews and Christians should be understood monotheistically. The Judeo-Christian Supreme Being invites angels to intercede with Him on behalf of humans to change the physical world. However, He does not allow angels to make those changes without His explicit permission. (3) Only the Supreme Being can independently change the physical world in non-physical ways. Thus, Jews and Christians sometimes "pray to various heavenly beings to intercede on their behalf with the one God in whom all power ultimately resides" (Sommer 147). But Jews and Christians do not pray for angels to independently change the physical world themselves. In contrast, Sommer observes that polytheistic "people pray to multiple deities because of a belief that multiple deities have their own power to effect change" (147). In other words, polytheists believe that, in addition to the Supreme Being, there are many subordinate non-physical entities that are unconstrained by the physical laws that normally constrain the movements of people and other physical objects. Ghanaian animists, for example, believe this is true regarding the life-forces of departed ancestors, especially royal ones. Thus a Ghanaian animist might explain "a mysterious malady in terms of, say, the wrath of the ancestors" (Wiredu 51). While "they derive ultimately from Onyame," the Supreme Being, the life-forces of departed ancestors have "mystical powers" (Gyekye 73), powers that can sometimes be "causes of action and change in the world" (Gyekye 79). Clearly, however, a Supreme Being cannot both allow some subordinate non-physical entities to intervene autonomously in physical events while also preventing any of them from doing so. At this point of discussion, then, either the Supreme Being experienced through animistic prayer cannot be viewed as existing independently of that experience, or the Supreme Being experienced through Judeo-Christian prayer cannot be so viewed. Unfortunately, the checking procedures that ordinarily establish the real independence of the objects of perceptual experience are not available for judging experiences in which God appears. In particular, we cannot judge such objects on the basis of predictions about their future behavior that can be seen as well as felt by any relevantly placed observer. The reason is that neither the Supreme Being of Judeo-Christianity nor that of animism satisfies these conditions. Indeed, no object of religious experience can be established as independently existing in the way independent existence is ordinarily established. In addition to experience, something else is necessary for viewing the Supreme Being in any religious experience as having independent existence—faith, for example. On the face of things, it is not surprising that faith is necessary for Christians with respect to the Supreme Being. While different Christian traditions provide different ways of understanding faith, all accept it as necessary for grasping the deepest truths about the Supreme Being. But the need for faith in addition to experience of the Supreme Being for regarding Him as real, as independent, does change a common way of understanding the authority of Scripture. Commonly, Scripture is understood as authoritative because its authors are regarded as inspired by the Supreme Being who was independent of the experiences He inspired them to have while writing Scripture. Given the above argument, however, faith in addition to experience was necessary even for the authors of Scripture to view the Supreme Being as independent of their experiences of Him. In other words, contemporary faith is based in part on ancient faith, not just on ancient events. This might seem a little surprising. (4) Notes

(1) This was not true of the

Pentecostals studied by

Luhrmann. Indeed, her index

contains no entry for "altruism,"

"positive social effects,"

"tolerance," "authenticity," or, for

that matter, "charity" or

"compassion."" The entry for "love"

refers only to God as "unconditional

love" and to the practice of "feeling

loved."

(2) An objection to this line of argument is that it implies an absurdity. One could object that all experiences, even those of the ordinary perceived world, result from brain activity; thus, if we reject the independence of the objects of religious experiences because they result from brain activity, we must also reject the independent existence of the ordinary objects of normal perceptual experiences. Such a rejection would seem absurd. To explicate John Locke's (1690) famous theory of representative realism, however, J. L. Mackie (1976) argues this is exactly what we should do. A normally perceived object should be understood as identical with the perceptions of it; and so nonexistent when not perceived. To account for correlations between seen objects and felt objects that evolve in predictable ways, Mackie introduces Locke's concept of material substance, now construed as groups of individual molecules. Groups of molecules cause us to perceive the objects we do while remaining entirely distinct from them. Their remaining distinct explains why the objects they cause us to see and to feel at different times are so well correlated even though not continuously existing. However, the groups of molecules that cause us to perceive an object are distinct from it, and the individual molecules that compose this group do not compose that object. This way of thinking is obviously strange and different from the commonsense theory that perceived objects cause us to perceive themselves as they exist independently of perception. However, C. W. K. Mundle (1971) and Amanda Gefter (2016) summarize some of the reasons why many neuroscientists now prefer representative realism to the commonsense theory of perception. The present author (1990) used Mackie's interpretation to explain how representative realism applies to religious experiences specifically. (3) In note 9 of his Appendix, Sommer supports this interpretation of Christian angels with the research of scholars focused especially on Deut. 4.19 and 32.8, Exodus 20.3, and Leviticus 18.25. (4) My thanks to Norm Robertson, an old friend who provided helpful guidance at several stages in this article’s development. Thanks also to the Editorial Advisory Committee, whose advice about the penultimate draft improved the article’s structure. Of course, any remaining defects are my responsibility alone. Works Cited

A'Ambrosio, Dan. 2014. "A Tale of the Trace." Adventure Cyclist (June): 42-44. English, Parker. 1990. "Representative Realism and Absolute Reality." International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 23: 127-145. Gefter, Amanda. 2016. "The Case Against Reality." The Atlantic.com (25 April). http://www.theatlantic.com/science archive/2016/04/the-illusion-of-reality/479559/ retrieved 5 January 2017] R. R. Griffiths & W. A. Richards & U. McCann & R. Jesse. 2006. "Psilocybin Can Occasion Mystical-Type Experiences Having Substantial And Sustained Personal Meaning And Spiritual Significance." Psychopharmacology 187 (July): 268–283. http://www.csp.org/psilocybin/Hopkins-CSP-Psilocybin2006.pdf retrieved 5 January 2017] Gyekye, Kwame. 1987. An Essay on African Philosophical Thought: The Akan Conceptual Scheme. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted by Temple University Press: Philadelphia, 1995. Locke, John. 1690. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Luhrmann, T.M. 2012. When God Talks Back. NY: Alfred A. Knopf. Mackie, J.L. 1976. Problems from Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Mundle, C.W.K. 1971. Perception: Facts and Theories. London: Oxford University Press. Pahnke, Walter. 1966. "Drugs and Mysticism." The International Journal of Parapsychology Vol VIII (No. 2, Spring): 295-313 [ https://www.erowid.org/entheogens/ journals/entheogens_journal3.shtml retrieved 5 January 2017] Penfield, Wilder. 1958. "Some Mechanisms Of Consciousness Discovered During Electrical Stimulation Of The Brain." Proceeding of the National Academy of Science 44 (2): 51-66. Pratt, James B. 1941. Can We Keep the Faith? New Haven: Yale University Press. Sommer, Benjamin D. 2009. The Bodies of God and the World of Ancient Israel. Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition. Wiredu, Kwasi. 1996. Cultural Universals and Particulars: An African Perspective. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. About the Author

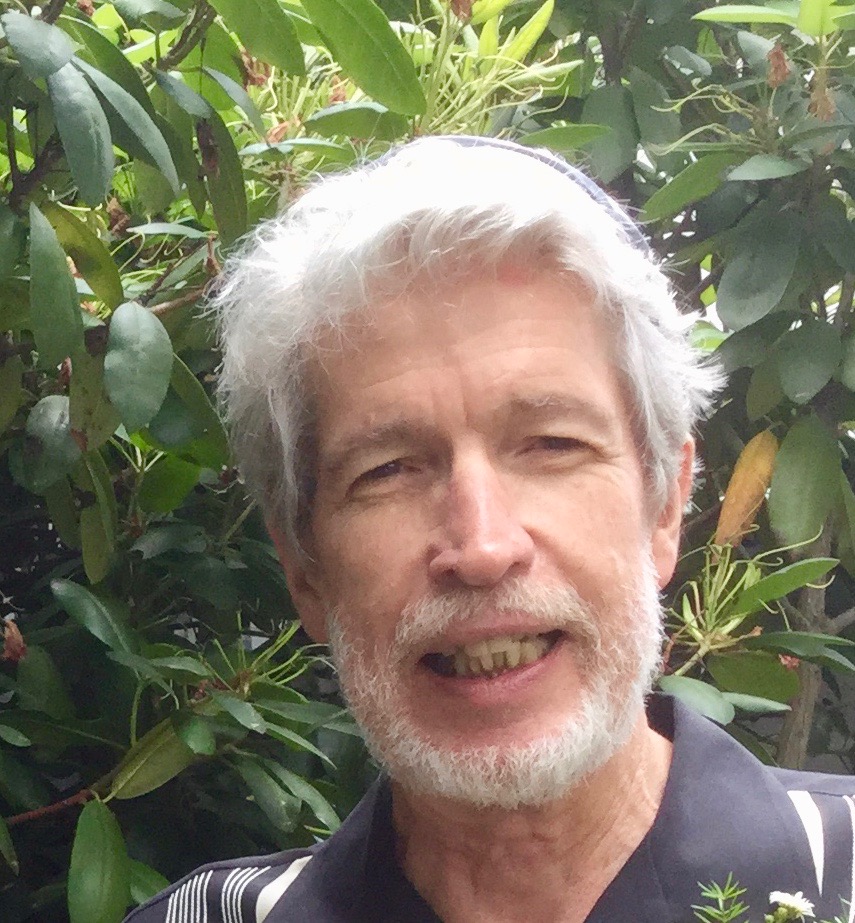

After controlling close air support as

a Marine First Lieutenant in Vietnam,

1968-69, Parker English received a

Ph.D. in philosophy from the

University of Western Ontario,

1974. He next built a log cabin

not far from Goderich, Ontario, before

felling trees for a logging camp 200

miles north of Lake Superior, 1975-77.

His first teaching job was at the University of Calabar, Nigeria, 1983-87. He retired from Central Connecticut State University, 2013, having had a teaching and research specialization in the emerging field of African philosophy. In addition to publishing What We Say, Who We Are and twenty articles or book chapters, English co-edited African Philosophy: A Classical Approach. English has hiked Canada's Bruce Trail, and canoed several of its wilderness rivers. Still an active cyclist, he has covered more than 10,000 miles bike-packing, including 800 honeymoon miles with his wife Nancy seven years ago. He aspires to competency with his new flatwater kayak. "God in Experience" was presented to the Portsmouth club on January 11, 2016. ©2019

by the International Association of

Torch Clubs |