The Official

Journal of

The North

Carolina

Sociological

Association: A

Peer-Reviewed

Refereed Web-Based

Publication

ISSN 1542-6300

Editorial Board: Editor: George H. Conklin, North Carolina Central University Board: Bob Davis, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Richard Dixon, UNC-Wilmington Ken Land, Duke University Miles Simpson, North Carolina Central University Ron Wimberley, N.C. State University Robert Wortham, North Carolina Central University

Editorial Assistant John W.M. Russell, Technical Consultant

Submission

Guidelines

for

Authors

Cumulative

Searchable

Index

of

Sociation

Today

from

the

Directory

of

Open

Access

Journals

(DOAJ)

Sociation Today

is abstracted in

Sociological Abstracts

and a member

of the EBSCO

Publishing Group

The North

Carolina

Sociological

Association

would like

to thank

North Carolina

Central University

for its

sponsorship of

Sociation

Today

®

®

Volume 6, Number 2

Fall 2008

Services Delivery for Displaced

Rural Workers:

A North Carolina Case Study of

the Theory and Reality of One-Stop: A Research Brief

by

Leslie Hossfeld*

University of North Carolina Wilmington

and

Donnie Charleston

North Carolina State University

and

Michael Schulman

North Carolina State University

Over the past decade and a half, human services systems have undergone significant change. The combined effects of devolution, policy changes, and demographic shifts have created a markedly different services structure in rural communities. Researchers are analyzing the impact of these changes on the welfare system in general, rural human services delivery, and workforce development programs (Southern Rural Development Center Welfare Briefs 1998-1999). However, there is a need for research that evaluates how these systems are performing under stress. The United States has felt the brunt of a number of natural and economic crises that are taking a devastating toll on many rural communities, especially in the South. The responses to these events have revealed some problems associated with coordination, logistics, and funding. The purpose of this policy brief is to provide guidance for policy makers and program officials who, in the aftermath of an economic disaster, find themselves coping with the challenges of workforce retraining, re-employment, and services delivery. Specifically, the aim is to identify necessary protocols – as they relate to workforce and human capital development - that can be implemented to mitigate the impacts of plant closings and the massive job loss that occurs because of severe economic downturns and rural restructuring.

From 1990 to

the present, North Carolina has suffered some of the worst job losses in

the nation (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2004). Because of its experiences,

it can serve as a valuable case study for analysis. This brief relies

upon data gathered from the Jobs for the Future project, a four-year community-based

participatory research collaborative between researchers, community organizations

and community agencies addressing massive job loss in Robeson County, North

Carolina. Data were collected from in-depth interviews and focus

groups with displaced workers, program administrators, and government officials.

Interviews were subjected to an in-depth analysis including triangulation

to identify common themes. In addition, information has been gathered

and compiled from government documents that help to illuminate the county's

and state's experience (www.povertyeast.org/jobs).

- The principal findings from the data are that: the nature of an economic crisis can expose gulfs between needs and available resources - thus hampering effective responses;

- disconnections between agencies are exacerbated and create problems for displaced workers and frustration for agency personnel; and

- during a crisis, the extreme variation among service seekers poses a challenge to the system as there is no one characteristic experience and thereby no single panacea. Based on this analysis, this brief makes a series of recommendations for policy makers and administrators aimed at strengthening rural communities by increasing their response capacity.

Background

From 2001 to

2003, almost one in ten rural displaced southern workers was a manufacturing

worker. This is five times the proportion of displaced rural workers who

were service sector employees (Bureau of Labor Statistics).

Although job loss is not evenly distributed across localities, the rural

south has disproportionately borne the impact due to its dependence upon

manufacturing.

Plant shut downs create a swell of displaced workers most of whom seek assistance from the local human services system. As these workers lose their jobs, they create pressure for already strained local services systems that have been undergoing an evolution over the past decade and half. The present configuration of local services systems reflects the consolidation that occurred as a function of the 1988 Workforce Investment Act (WIA).

Congress passed the WIA which required the formation of locally based one-stop service systems to deliver the majority of employment and training services funded by the federal government (US Department of Labor). The one-stop career system was envisioned as a system that would consolidate programs, resources, and services such as unemployment insurance, state job services, public assistance, training programs, and career services. Four principles guided the system's development:

- Universal access to all population groups including both job seekers and employers;

- Customer choice based on the consumers' evaluation of his/her needs;

- Service integration and;

- Performance-based accountability (Workforce Investment Act 1998).

As is often

the case, the model that guided the design of the one-stop programs was

based on an urban context. Although the policy included provisions

and directives for customizing the system for local implementation, there

have been numerous difficulties with implementing the WIA one-stop programs

in the rural context (Workforce Investment Act 2002).

Programmatic and financial concerns have been found to hamper effective implementation because of concerns over loss of program integrity and identity (Workforce Investment Act 2000). In particular, the Government Accounting Office indicates that infrastructure limitations, antiquated computer systems, and conflicting reporting requirements and program definitions have plagued WIA one-stop programs.

North Carolina's implementation of the one-stop system is heralded as being advanced in terms of its approach to its system design and the fact that it is one of a few states that have made a serious attempt toward integrating the range of social and human services into the framework. Although the act mandates participation of a number of federally funded programs, North Carolina's implementation requires the participation of additional partners: all programs formerly supervised by the Employment Security Commission: Vocational Rehabilitation; employment and training services for the blind, youth, disable and Native Americans; the Welfare-to-Work program including Temporary Assistance to Needy Families and the Food Stamp Program.

The far reach of NC's plan combined with the state's large scale job loss, makes it an ideal candidate to examine how this system functions under stress. It is very important to distinguish between large-scale job loss and episodic job loss. North Carolina has been particularly good at stepping-in to address mass layoffs like the closing of Pillowtex in Kannapolis in 2003 when 5,500 workers were laid off. The state has had a weaker response to episodic job loss in counties where job loss remains constant, yet not necessarily a mass layoff in the thousands.

From 1993 to 2003, the state lost a total of 205,355 jobs. Many of these were in the manufacturing sector, a sector that has provided economic stability for individuals and rural communities throughout the 20th century. Yet, since the mid-1990s, this stability has eroded. With the implementation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the restructuring of apparel and textile manufacturing thousands of North Carolinians have been displaced. In 2001, the number of manufacturing workers affected by mass layoffs doubled from 22,568 to 44,476 (North Carolina Employment Security Commission).

Considering the fact that North Carolina's textile plants are on average larger and employ vastly more employees than those in other states, this presents a huge problem. These policies combined with technological advances have contributed to the state's alarming job losses.

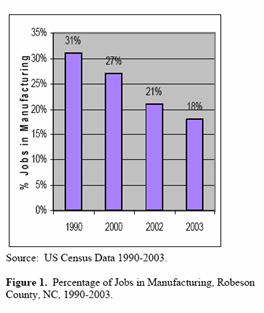

More so than any other county in the state, Robeson County, North Carolina has felt the sting of waves of manufacturing plant closings. The county is situated in the economically depressed southeastern region of the state, and has been a persistent poverty county since 1970. Persistent poverty counties are those counties that have had poverty rates of 20% or more in each decennial Census between 1970 and 2000 (RUPRI 2007). In Southeastern North Carolina there are four counties of persistent poverty: Bladen, Columbus, Robeson and Hoke (USDA-ERS 2007); each of these counties is adjacent to Robeson County. Robeson County is one of the most racially diverse rural counties in the state and nation. It is the home of the Lumbee Native American group which comprises 38% of the population. It has a large, poor, African American population (25%) and a traditional white, rural population (33%) as well as a fast-growing Latino population estimated at 5% (US Census Bureau 2007). In 2007, Robeson County had the fourth highest poverty rate in the nation for counties with populations between 65,000 and 299,000 (US Census Bureau 2008). Between 1993 and 2003, Robeson County lost 41% of its manufacturing jobs – a total of 8,708 unemployed residents (Estes, Schweke, Lawrence 2003). Considering that in 1993, manufacturing accounted for 31% of all jobs in the county, this loss represents a significant portion of the county's economic base. In the year 2003 alone, there were nine reported plant closings (North Carolina Employment Security Commission 2004). Job loss in Robeson County reflects a sustained, episodic pattern of job loss, wherein layoffs may range from 100 to 2000, yet not necessarily at one time, such as the mass layoffs in Kannapolis, North Carolina in 2003.

The effects of this job loss extend beyond the manufacturing sector and beyond the loss of jobs and income. Over the time period examined, the multiplier effect of manufacturing job loss has impacted other sectors of the economy. Accounting for both part-time and full-time jobs, the estimated loss of 8,708 manufacturing jobs in Robeson County resulted in a total reduction in regional employment of 18,345 jobs over ten years (Hossfeld et al. 2004a).

By 2004, the cumulative 12-year impact of jobs, income and indirect business taxes lost to the 5 county commuting-region was $4,784,293,080 due to the job losses in Robeson County (Hossfeld et al. 2004b). By 2004 regional governments were collecting $39 million less per year in indirect business taxes. There was a cumulative 12-year impact of $220,897,215 reduction in indirect taxes paid by businesses (Dumas 2004). As a function of these losses, the revenues the county would have ordinarily counted upon were drastically reduced. The quandary Robeson County found itself is an all too familiar scenario: limited revenue sources and a diminished capacity of citizens to support the government.

The two principal sources of county government revenue - sales taxes and property taxes collections – were substantially reduced. Without this source of revenue, the county was hampered in its ability to respond to the needs of its citizens (Hossfeld et al. 2004a).

The problems associated with delivering effective services during a crisis go beyond the economic. Inasmuch as one of the main responsibilities of local government is to administer human services, the financial strain caused by plant closings and job displacement precipitates other system problems. In the section that follows, we consider policy recommendations based on the Robeson County case study.

Policy Recommendations

Policy Recommendation 1.

Critically examine funding streams and the strength of local capacity to

weather a stress event.

"Property tax collections in Robeson County…are in the last few years the lowest of any county in North Carolina…and a lot of that is because people very well may not have had the money to pay their taxes."

County Official

Developing

a common definition of what a major incident is and identifying the types

of financial, social, and physical supports that will be needed is of critical

importance. In North Carolina, as is the case in many states, local finances

and public infrastructure help to maintain the foundation of the one-stop

system. Because of this fact, the differential capacity of rural

areas as compared to urban areas hinders the successful implementation

of one-stops. In the southeast region of North Carolina, counties

like Robeson have very high financial commitments for overall human services

expenditures because of their high poverty rates, high incidence of female

headed households, and low median family incomes. Plus, one-stops tend

to be more effective in urban areas where the consolidation of services

may be easier given the closer proximity an urban area may provide; not

necessarily the case in rural areas where physical distance creates even

greater difficulties for capacity to provide one-stops. Furthermore, North

Carolina counties must support the local Medicaid program, up to 1/3 of

a county's budget in many cases (Bonner and Kane 2006). The financial

stress experienced by already economically burdened rural counties is a

barrier that is not easily overcome.

The increase in services demand as a function of plant closure strains an already tapped services system. The already high expenditures on human services prevent the subsequent reallocation of funds to new needs. Moreover, examining the disbursement of federal funds by region indicates that there is a disjuncture between the level of need and the actual drawdown of funds from federal programs (Giermanski and Lodge 2000).

At the organizational level, service providers in the area reported an increase in staff burnout and turnover as job displacement increased the workload and stress of agency employees. Rural areas have traditionally functioned as training grounds for new workers who then leave for higher paying urban areas. This exodus was, exacerbated during the economic crisis created by plant closings.

Furthermore,

one-stops are difficult to sustain in regions where episodic job loss occurs.

One-Stops tend to be more effective during massive layoffs, rather than

sustained, episodic, drawn-out layoffs that may continue for a county over

a period of several years, rather than at one moment in time. A critical

flaw with many Workforce Development strategies is the lack of understanding

of the rural experience and how job loss differs significantly in rural

versus urban areas. The long, drawn-out episodic job loss for counties,

such as Robeson, creates unique challenges for one-stop programs.

Policy Recommendation 2.

Maximize the outcomes of efforts by using a multi-dimensional approach

to service delivery.

"…our worker turn over is large in the food stamp section in the last twelve months we've had about, a fifty percent turn over." Social Service Administrator

"there are no jobs here, not even for me to get seven hours a week anywhere."

Displaced Worker

"My husband works first shift and I work second... when the kids get out of school he gets home…so at that point I can go to work so it manages.Unemployed rural workers participate in various survival strategies. Whereas, educational programs have been identified as the preeminent tool for coping with the needs of displaced workers, as mandated by the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) capitalizing on alternate strategies by first understanding and then incorporating these paths into program structures should prove beneficial. The WIA reflects the “education is key” approach and short term job retraining is a prominent feature of the program. However, reliance on one model ignores the reality that there are multiple post-displacement trajectories and that no one model will achieve maximum penetration and effectiveness. The trajectories of worker paths [post-displacement] are a function of both formal and informal social networks. Interviews revealed that the multiple paths included: the long-term unemployed, part-time commuter workers, kinship based family care work, entrepreneurial endeavors, and those taking advantage of training/education.

Displaced Worker

"By the time I come out of school, I should be able to make money. Regardless if anybody hires me or not…I have to be able to convince somebody." Displaced WorkerThe crucial flaw in the system is the lack of sufficient attention paid to developing an accurate picture of the displaced worker, and an identification of his/her true needs. As is the case with many human services systems, there has been a shift away from the one-on-one case management model to a “consumer” model based largely on a computer-assisted self-service model. Notwithstanding the efficiencies gained by such a system, for a system based on consumer choice to work, there must be sufficient information about available services [for the individual to successfully navigate], and the technology must be accessible for consumers. As evidenced by the state's own evaluation, most areas have a long way to go before this outcome is realized (North Carolina JobLink Center 2000). System administrators from across the state highlighted the problem of an inter-agency collaboration because of different technologies and infrastructure capabilities (North Carolina Commerce 2004). North Carolina is at present examining alternative approaches to service delivery and implementing more redundancy into its system through client-focused approaches.

Policy Recommendation 3.

Critically examine and strengthen interconnections between agencies and

dissolve barriers to effective collaboration.

"…we need to start at the state level trying to figure out a way that we can come together."Many of these problems between agencies may go unnoticed until the stress of an event exacerbates these conditions. Although it is marketed as one entity, the one-stop is actually a network of agencies. To achieve the expected outcomes, each agency must recognize the necessity of acting as a support beam of a system as opposed to solitary entity. This requires a high level of collaboration marked by consensual, coequal, interdependent relationships. However, individual funding streams, governance structures, and accountabilities (different constituencies) creates an environment where effective collaboration is difficult. Reports from regional meetings of service providers reveal that networks are characterized by a lack of cohesion and are routinely encountering issues of conflict between partners (North Carolina Joblink 2000).

Administrator

This lack of cooperation, underscores the fact that there is little if anything in place to compel agencies to collaborate. There is therefore a need to go beyond formalized agreements void of substance. The dominant mode of engendering collaboration is the establishment of memorandums of understanding and agreement. However, MOUs and MOAs rarely translate into true collaboration without creating linking mechanisms between agencies (e.g., cost sharing, unified information systems, and client monitoring across services).

Even with these mechanisms in place, effective collaboration will not occur without proper guidance and leadership. Typically policies assume that the necessary knowledge base for successful implementation exists at the local level, but the magnitude of an economic crisis can overwhelm the local social service system. This state of affairs can throw a network into a free fall wherein administrators are grasping for straws as their agencies try to stay afloat. In stark contrast to the caricature of local agencies as ‘autonomy seeking entities,’ surprisingly agencies reported a desire to have clearer objectives and guidance provided to them by governing authorities.

Collaboration should include design templates based on research informed best practices identified from other localities and states. This paper highlights one community's experience in coping with economic disaster. With these lessons in mind, the state has started to create a more comprehensive and targeted approach for displaced worker service delivery. Some of the more innovative and promising approaches that we consider best practices are highlighted below:

Best Practice 1: Multidimensionality

The North Carolina Employment Security Commission is collaborating with an agency that provides technology-supported case management and resource information for transitioning workers. Through telephone counseling and referral, Connect Inc. (http://www.connectinc.org/htmls/faq.html) increases worker job acquisition and supports job retention by focusing on career development, financial planning and asset accumulation. Connect Inc is expanding its services through the state-wide Next Steps program. Through conference calls, case managers connect displaced workers to job opportunities, fax resumes on behalf of workers and provide tailored support to workers. The North Carolina Employment Security Commission is also working to assist displaced workers in obtaining the federal health care subsidies from the Trade Act of 2002 (www.ncesc.com/individual/training/taa.asp). The NC Rural Center is sponsoring Project New Start to marshal the resources of local organizations so that they complement the services provided by public workforce training and job placement agencies. In addition, the state has partnered with the Rural Center to develop an entrepreneurship based program - New Opportunities for Workers Program – designed to strengthen displaced worker's potential as entrepreneurs. Although these programs are not implemented state-wide, the fusion of the state's resources with the strengths and strategies of other agencies helps to address the problems associated with uni-dimensional service delivery.

Best Practice 2: Leveraging Community Capacity

In Robeson County, a community-based, nonprofit organization, The Center for Community Action (www.povertyeast.org/jobs) is engaged in community based participatory research to document the process by which individuals, families and communities develop survival strategies. They were instrumental in connecting displaced workers with decision makers by organizing forums to highlight their concerns and needs yielded positive outcomes for displaced workers (including a forum with the US Congressional Rural Caucus). The Center has created The Women's Economic Equity (WEE) project, funded by Z. Smith Reynolds. This is a three-year demonstration project that focuses on supporting and developing the economic security of rural women in North Carolina. Through training, career development, coaching, and networking, WEE matches employers to retrained female displaced workers. (See www.povertyeast.org/jobs for full research reports.) In Guilford County, Guilford Technical Community College has developed the Quick Jobs With a Future program that provides short, intense, skills-training courses to prepare displaced workers for new jobs (www.technet.gtcc.cc.nc.us/quickjobs). Courses are affordable, provided at a variety of locations and customized to a specific trade skill.

Best Practice 3: Shoring Up Deficiencies

Interventions by outside

parties can help to achieve positive results. The NC Rural Center

(www.ncruralcenter.org), a private, non-profit organization has been engaged

in a program aimed at shoring up the statewide system of services supports

for displaced workers. It has brought together leaders from across

the state to address the problems of displaced workers. The Rural

Center guided the NC Dislocated Workers Taskforce whose efforts produced

a plan of action (see www.ncruralcenter.org/

pubs/GaF%205-31-05.pdf) and

a set of policy recommendations guidelines (see www.ncruralcenter.org/

pubs/back_on_track_09_06.pdf).

The impartiality of such an organization can often help to mitigate problems

associated with barriers to collaboration by creating a sense of shared

commitment.

Each of these strategies represents a step in the right direction. Nonetheless, if they are to be sustainable, the addition of a comprehensive evaluation component is of crucial importance. The present preoccupation with job placement numbers and income attainment as outcome factors is limiting. Ideally, a comprehensive evaluation should be built into the design of a one-stop system. However, as is often the case, the evaluation component is left to individual agencies many of whom establish their evaluation protocols post-program implementation. It is necessary to move beyond the individual organization evaluation to an evaluation that looks at system processes and outcomes: determining whether interlocking mechanisms are in place, establishing whether they are functioning appropriately; determining the adequacy of redundancy mechanisms and identifying potential points of weakness; and making projections of funding allocations and contingencies beyond usual levels of utilization.

When initially designed, the one-stop system was characterized as a bridge linking workers with the needed services and supports. Although the analogy is apt, the system at present does not provide an adequate transitional structure for many who find themselves in need. What is needed is a shoring up of the structure such that it can withstand both the periodic and the ongoing storms of economic crisis and restructuring.

Footnote

*Please direct all correspondence to Leslie Hossfeld, Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, 601 South College Road, Wilmington, NC 28403, HOSSFELDL@uncw.edu ; Office: 910-962-7849. of Sociology, Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, 601 South College Road, Wilmington, NC 28403, HOSSFELDL@uncw.edu ; Office: 910-962-7849.

References

Bonner, L., Kane, D. 2006. "Counties Hope for Medicaid Help" News and Observer. October 17.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2004. Mass Layoff Statistics. http://www.bls.gov/schedule/ archives/mmls_nr.htm#2004.

Dumas, C. 2004. "The Economic Impact of Manufacturing Activity Decline in Robeson County, NC 1993-2003." Research Report, Center for Community Action: Lumberton, North Carolina.

Estes, C., Schweke, W. and Lawrence, S. 2003. "Dislocated Workers in North Carolina: Aiding Their Transition to Good Jobs." North Carolina Justice and Community Development Center.

Giermanski and Lodge. 2000. "An Analysis of NAFTA and Textile Closings in North Carolina." Journal of Textile Apparel, Technology and Management.

Hossfeld, L., Legerton, M., Kuester, G. 2004a. "The Economic and Social Impact of Job Loss in Robeson County North Carolina 1993-2003." Sociation Today 2(2).

Hossfeld, L., Legerton, M. Dumas, C., and Kuester, G. 2004b. "Robeson County Job Loss: Center for Community Action Report." Lumberton, North Carolina.

North Carolina Commerce. 2004. "The Journey to Integrating Workforce Development Services in North Carolina." http://www.nccommerce.com/workforce/reports/

North Carolina Employment Security Commission. 2004. Mass Layoff Data, Labor Market Information Division. http://www.bls.gov/ces/

North Carolina JobLink. 2000.

"North Carolina JobLink Career Centers An Appraisal of Progress."

http://www.mdcinc.org/

docs/Joblink/Career_Center_Feedback_

Paper.pdf

Southern Rural Development Center. 1998-1999. Center Welfare Reform Briefs. http://srdc.msstate.edu/publications/reform.htm

Workforce Investment Act. 1998. Public Law 105-220 August 7, 1998. 112 Stat.936 Public Law 105-220, 105th Congress.

Workforce Investment Act. 2002. Better Guidance and Revised Funding Formula Would Enhance Dislocated Worker Program, GAO-02-274. February 11.

Note: Several links used in this article no longer function and are already history. You may find updated references by using a search engine.

Return to Sociation Today

Fall 2008

©2008 by the North Carolina Sociological Association