Sociation Today®

ISSN 1542-6300

The Official Journal of the

North Carolina Sociological

Association

A Peer-Reviewed

Refereed Web-Based

Publication

Fall/Winter 2015

Volume 13, Issue 2

| Building Community in

Hard Times:

Food Insecurity, Food Sovereignty and the Development of a Local Food Movement in Southeastern North Carolina by

Leslie Hossfeld

Mississippi State University and Julia Waity University of North Carolina Wilmington Introduction

Food and community are inextricably tied

together. The community where food is

produced, who produces it, the rituals and

customs that surround the food we eat are

central to all regions and all

communities. Southeastern North Carolina

is no different: small family farms once

dominated the entire North Carolina

landscape, particularly in the Southeast

where the rich, fertile soil made farming

central to community life. Southeastern

North Carolina has a long history and

connection with agriculture, which served

as the primary economy in many counties

for decades where food production has

shaped the region and its rural

communities and is deeply embedded as part

of the history, economy, and culture of

the region. While agriculture still exists

in this area, its form has changed.

Replacing the small family farms that were

intrinsically linked to the community and

land are large agribusiness industries

that have little ties to the region beyond

economic incentive.

Poverty is also deeply embedded and is a defining characteristic of this corner of the state. Once referred to as the "vale of humility between two mountains of conceit," (1) North Carolina transformed itself from its humble origins to a progressive state embracing the new millennium. From the boom of the Research Triangle to the financial banking hub of Charlotte, North Carolina stood out on many indicators of progress, prosperity and leadership. Yet the very problems that have plagued the state for centuries endure, and the residue of these is the very issue facing Southeastern North Carolinians. Persistent poverty, low incomes, and enduring racial inequalities are the age-old problems afflicting the region under study. The rural, small town South captures much of what Southeastern North Carolina has traditionally been, and is, today. Spatial Context

The word community can have many wide

ranging definitions. For this paper, we

define community as based on the

geographic boundaries of the Southeastern

North Carolina Region, as well as the

unique history of the region and the

people who live in it. This community is

made up of primarily rural counties and

one urban center, both of which have high

rates of poverty and food insecurity.

Specifically relevant to our case study,

we can break this down into low-income

farmers in rural areas and low-income city

residents who lack access to affordable

produce. Connecting these two groups is a

way to revitalize communities, especially

in light of those lamenting the current

decline of community (for example, Putnam

2000).

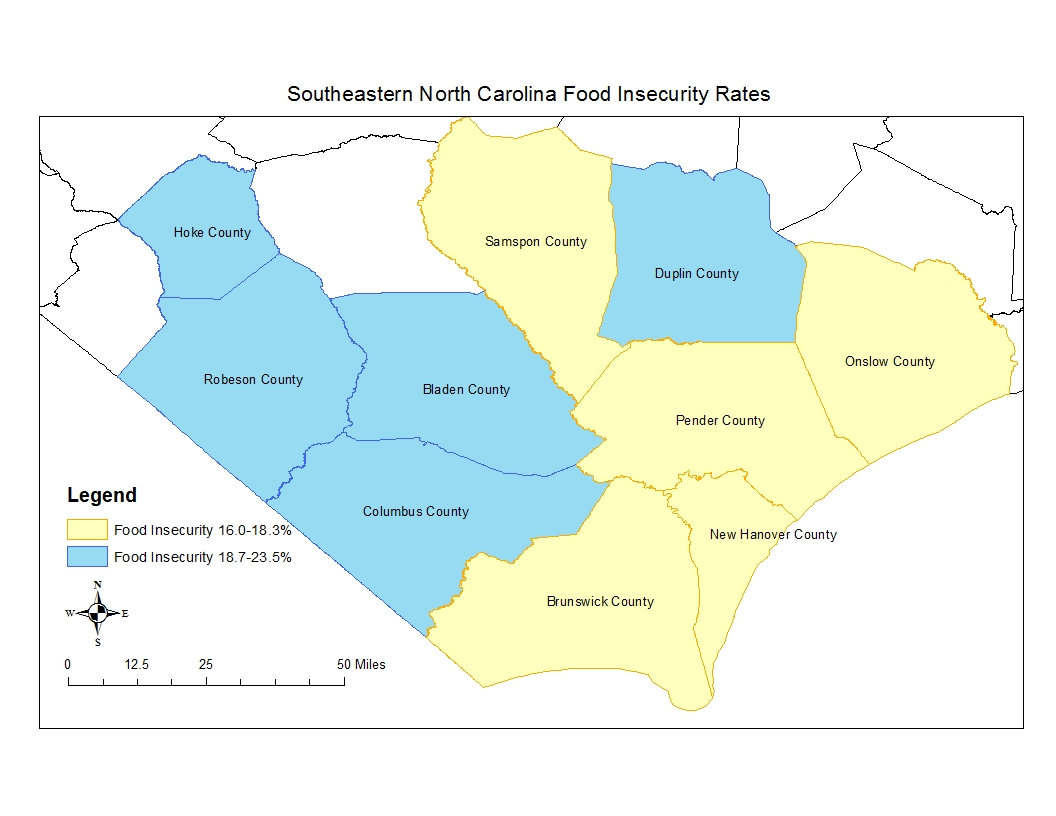

In 2013, the poverty rate in the United States was 14.5% (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor 2014). This was significantly higher in North Carolina at 17.5% (ACS 2009-2013 data). The state of North Carolina has 10 counties of persistent poverty, and Southeastern North Carolina has three of those counties: Bladen County, Columbus County, and Robeson County. It is important to note that persistent poverty is a USDA measure that captures the dimension of time and so these are counties that have poverty rates over 20% over the last 40 years, measured by the decennial census. They are also adjacent, so if you are unable to find work in your own county, going to the next county does not help either. The counties that run along the coast are referred to as the Gold Coast, and while they have lower poverty rates, their coastal wealth masks incredible pockets of deep poverty as you move away from the coastline. Persistent poverty in this region is largely due to economic restructuring and manufacturing textile job loss and farm loss. The community of Southeastern North Carolina has a unique spatial context. It is the most ethnically diverse multi-county region east of the Mississippi River with a traditional, rural, African American and white population, a large Native American population, and a very fast growing Latino Population. There is only one urban county in the region and this includes the city of Wilmington. It is part of the Black Belt located in the rural south, which has been referred to as a "forgotten place" due to a lack of economic development (Falk, Rankin, and Talley 1993). This is especially true in Southeastern North Carolina where a lack of economic development and widespread job loss has left behind a region with high rates of poverty, food insecurity, and the challenges that go along with that. Southeastern North Carolina comprises ten counties: New Hanover, Brunswick, Columbus, Robeson, Hoke, Pender, Onslow, Sampson, Bladen and Duplin. The North Carolina Rural Center designates all these counties rural except New Hanover. All are part of the Southeastern Economic Development Partnership, except for Duplin and Onslow, members of the Eastern Economic Development Partnership. The North Carolina Department of Commerce ranks counties in the state along three Tier designations representing economic well-being. Tier 1 designations reflect the most distressed counties in the state; in Southeastern North Carolina Bladen, Columbus, Hoke and Duplin are Tier 1 counties. Tier 3 designations represent the least distressed counties in the state; in Southeastern North Carolina, New Hanover, Pender and Brunswick counties have Tier 3 designations. Counties in-between the most and least distressed counties have Tier 2 designations; Sampson, Duplin, and Onslow reflect these designations for Southeastern North Carolina. The history of agriculture in this region has been that of small, family farms. The 7th Congressional District, serving all of Southeastern North Carolina, lost 54,866 acres of farmland between 2002 and 2007 (USDA Department of Agriculture, 2007 US Census of Agriculture). North Carolina has lost more farms than any other state in the nation. The decline has been most pronounced among African-American farmers who had a 15% decline in NC from 2002-2007. In spite of this loss, the 7th Congressional District continues to rank first in agricultural sales in North Carolina with the total value of agricultural products sold at $2,520,862.00 (2007 Census of Agriculture). This district ranks as the twenty-sixth most productive congressional district in the nation. Despite that fact, 60 percent of the farms (2,905 of the 4,809) in the 7th District had less than $20,000 in farm sales in 2007, indicating that these were smaller family farms. Limited-resource farmers often lack resources and/or training and face enormous challenges as competition from industrial agriculture and food imports make it increasingly difficult for them to maintain a livelihood and sustain their farms. Add to this the aging farmer: the average age of Southeastern North Carolina farmers is 57. Many small farmers lack the resources and time to market and promote their farm businesses. The nature of their business requires them to focus on maintaining their farms, leaving little time to find new markets for their products. Institutions, on the other hand, lack the time or resources to procure local foods for their establishments. It is much more efficient, and at times economical, to purchase from large food vendors and thus small-scale, family farmers have had limited access to the large agribusiness model of food distribution. Food Insecurity and

Access to Food

There are several important indicators of

material deprivation. Not everyone living

in poverty is exposed to these

deprivations, but they are more common

among the poor population. These include

lack of adequate food, affordable shelter,

heat, and electricity, and other related

deprivations. Lack of adequate food, or

food insecurity, is the main focus here.

Food security is defined by the USDA as

"consistent, dependable access to enough

food for active, healthy living"

(Coleman-Jensen, Gregory, and Singh 2014).

In 2014, 14 percent of Americans were food

insecure (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2015). The

food insecurity rate for North Carolina is

significantly higher at 17.3 percent, the

fifth highest food insecurity rate in the

nation (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2014). Most

counties in Southeastern North Carolina

have food insecurity rates that are even

higher than the North Carolina average,

especially the persistent poverty

counties. Food insecurity is measured by a

series of questions developed by the USDA

that range from questions asking about

sufficiency of money for food to skipping

meals because there was not enough money

to buy food. Those who answer yes to six

or more questions are considered to have

very low food security (about 5.6 percent

of Americans).

The Great Recession had a profound impact on food insecurity. Prior to the recession, food insecurity rates were around 10 or 11 percent. Rates started to rise drastically in 2008 to a peak of 14.9% in 2011. Food insecurity rates remain much higher than before the recession. The hard times of the recession that caused this spike in food insecurity have especially impacted these persistently poor counties. The majority of counties in this region are rural counties, which have higher food insecurity rates (15.1%) than suburban areas (12.1%), although not quite as high as central city areas (16.7%) (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2014). Programs have expanded to keep pace with the recession’s impact.  Lack

of access to food is another issue faced

by many Southeastern North Carolina

community members. Areas that lack

access to grocery stores are often

considered food deserts. Food insecurity

is often associated with living in a

food desert. Food deserts are defined by

the USDA as areas "without ready access

to fresh, healthy, and affordable food."

While food deserts may not directly

cause food insecurity, they are good

indicators of areas where food

insecurity is more likely (Morton et al.

2005). These areas often have easier

access to fast food and convenience

stores which can have a negative impact

on the health of community members.

These same areas often also lack access

to food pantries and soup kitchens which

might be used to supplement limited food

resources. Despite concerted efforts,

food assistance agencies often do not

have the resources to provide fresh

produce to clients.

Local

Food Systems Initiatives

The

Southeastern North Carolina Food Systems

(SENCFS) Program (also known as Feast

Down East {2} ) began in 2006 as an

economic and community development

initiative in response to the massive

job loss in the region’s agricultural

and manufacturing sectors, and the

growing poverty rate. Through grassroots

organizing and an intentional focus on

poverty alleviation and community and

economic development, Feast Down East

(FDE) has advanced into a partnership of

public and private institutions and

agencies in eleven counties and includes

both rural and urban counties to

maximize market opportunities and keep a

greater percentage of the food dollar

within Southeastern North Carolina and

increase local and regional wealth

through the multiplier effect of

expanded markets, sales, and profits.

The governance of FDE is democratic, farmer driven and supported by public and private service providers and businesses. The FDE Advisory Board is racially, geographically and sector diverse, including farmers, institutional buyers, educators, and policymakers. The Board is representative of the demographic composition of Southeastern North Carolina. Cooperative Extension agents in each county are directly engaged in local and regional planning, service provision and governance. The mission of FDE is to join institutions, agencies, farmers, businesses and consumers together to support, coordinate, expand, and sustain the production and consumption of healthy, local foods, particularly by and among limited resource farmers and limited resource consumers; and create an economically-viable, regional food-system and public/private partnership that benefits farmers, businesses, food services, and consumers and ensures access to healthy, affordable food by all consumers in Southeastern North Carolina. FDE is principally committed to increasing the capacity of limited resource farmers in becoming resourceful farmers and in supporting limited resource communities in advancing their own food security. Between 2006 and 2009, FDE completed research and local food assessments that identified seven major elements and needs in a regional food system in Southeastern North Carolina. These are: (1) profitable private and public markets for local food sales; (2) comprehensive support for and engagement of limited resource farmers and measurable outcomes to becoming resourceful farmers; (3) the processing and distribution of local foods for year-round sales and consumption of healthy foods; (4) a highly diverse and strong, public- private partnership; (5) food security and engagement of low and moderate income consumers in the 29 food deserts in the region; (6) the establishment of food policy councils that engage all stakeholders in the coordination of local food production, processing, distribution, sales, and consumption; and (7) significant public and private financial and nonfinancial support. The goals of poverty reduction, engagement, and empowerment of limited resource farmers (defined by the USDA as socially disadvantaged farmers and in this region primarily African-American and women farmers) and consumers are the foundation and beneficiaries of the system’s development and programs. FDE has created a comprehensive regional food system based on key partnerships throughout the region. Major partners and their roles are: (1) North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service, which provides farm support services including Good Agricultural Practices training as well as Nutrition Programs for low-income consumers; (2) Community Colleges—small business training providers; (3) child nutrition directors in the public schools and universities—food purchasers and preparers; (4) Wilmington Housing Authority that assists in creating programs that provide training and nutrition classes for low-income consumers in local food deserts; (5) Aramark local food service provider for University of North Carolina Wilmington and food purchaser & buy local educator; (6) Feast Down East Processing and Distribution Program, with 40 limited resource farmers, producers and distributors of local, healthy food; (7) Farmers’ markets and direct farm product outlets with Feast Down East as agent for eight markets; (8) Feast Down East Food Corps service member for Brunswick and New Hanover counties working in schools to expand nutrition awareness and community gardens; and (9) Feast Down East VISTA service members, who address food insecurity in the region. Low-income consumers and farmers have been actively engaged in FDE since its beginning. Both individuals and organizations involved in FDE attended monthly planning and implementation meetings in the Wilmington area. FDE limited resource farmers, predominately African-American and women farmers, lead and benefit from the work of the FDE Local Food Processing and Distribution Center created in 2012. The FDE Processing & Distribution Center is a USDA-Designated Food Hub located in Burgaw, NC. The center works primarily with farmers within a 50 mile radius of the hub. The food is aggregated and distributed to the Wilmington markets, which are approximately 30 miles from the center. This FDE Food Sovereignty program is one example of an initiative that increases community food security by addressing underlying causes of persistent poverty and addresses poverty through a program that increases income and food security. Feast Down East identified a major shortcoming of the national local food movement realizing that the national movement had largely become an experience for middle class consumers with discretionary incomes. In response to this, Feast Down East created its Food Sovereignty Program whereby limited resource consumers increase their access to fresh and affordable local food and gain knowledge and skills in developing and managing Fresh Markets in direct cooperation with producers. The Food Sovereignty Project links rural limited resource farmers in Pender, Brunswick, and Sampson County to urban low income public housing neighborhoods (situated in 8 USDA designated food deserts) in Wilmington, through a public housing Fresh Market that provides healthy, local food to low income, food insecure residents. Feast Down East ensures that healthy, affordable local food is placed and kept on the shelves of low-income consumers while also directly generating additional income that assists limited resource farmers in becoming resourceful farmers. Feast Down East has a long-standing partnership with Wilmington Housing Authority (WHA) through a community campus co-created by the co-founder of Feast Down East. One of the anchor programs has been a community garden and nutrition program for children and family members to connect with local farmers, local chefs and nutritionists on the importance of eating healthy foods. The ultimate goal of this program is to ensure food insecure communities have control over their own food security and have access to healthy, affordable food. Through this program, limited resource farmers increase their production and revenue and acquire additional skills and supports needed to become resourceful farmers. Limited resource consumers also learn leadership skills in coordinating their local fresh markets and direct engagement with farmers and their farms. The project transforms the entire relationship of low-income consumers with their own health, the food that they consume, and the farmers and farms that are its source. The FDE Food Sovereignty Program builds a circular system of mutual support and sustainability that improves the well-being of their livelihoods and community. An underlying principle of the project is that limited resource food desert consumers should benefit from the local food movement through targeted projects like the FDE Food Sovereignty Program that ensures access. The Feast Down East Food Sovereignty Project (3) ensures positive changes in knowledge, skills and empowerment of public housing residents in participating in the program through nutrition workshops and a Leadership Training Certification program for Food Sovereignty participants in an effort to ensure sustainability of the project and increased community ownership over food access and demand for food security. The project increases revenue for limited resource farmers that ensures sustainability of their family farms and builds on local assets of African American heritage farming. Relationships between grower and consumer have developed through farm heritage tours and gleaning programs. The FDE Food Sovereignty Fresh Markets have SNAP/EBT (4) access for purchasing. In addition, consumers have access to an Affordable Produce Box (similar to a CSA-Community Supported Agriculture box), and nutrition classes "Eat Healthy. Eat Local. Eat Well" that provides low-income residents with educational lessons on various nutrition/cooking related topics through interactive activities, cooking demonstrations, guest speakers and field trips. Low-income residents have the flexibility to order the foods they like and learn about new foods with seasonal recipes, which are included in their boxes. Creating the produce box programs enables Feast Down East to expand the program in a sustainable manner. Orders are taken from residents on Tuesdays each week and are delivered on Thursdays. The food orders to the farmers are incorporated into the Fresh Market orders for the week and the food is delivered and distributed the same day by the FDE Processing & Distribution Center. The additional food needed for the Friday Fresh Markets is stored in the refrigerator to be sold the next day; the system maximizes resources. Feast Down East increase sales for limited-resource farmers through the expansion of the Fresh Market and Affordable Produce Box Programs. The FDE food desert Fresh Markets welcome participation from the general public to sustain the markets. To

support and sustain this project, FDE

developed a Marketing and Advertising

Campaign, which highlights FDE farmers

and the FDE Food Sovereignty Program.

Through radio ads, consumers in the

region are educated on the importance of

buying local and supporting the efforts

of FDE to increase access to healthy

local foods in low-income communities.

FDE radio spots highlight local farmers

focusing on the personal story of the

farmer, with farmers sharing their

thoughts on supporting local

agriculture. The ads also highlight the

non-profit work of FDE: to increase

access to healthy food within low-income

communities.

Community

Food Systems – Building Community in

Hard Times

The

framework for the FDE initiative mirrors

the concept of ‘community food systems’

defined in a guidebook created by

Cornell University entitled, "A Primer

on Community Food Systems," in which the

authors define a community food system

as a,

food system in which food production, processing, distribution and consumption are integrated to enhance the environmental, economic, social and nutritional health of a particular place. The concept of community food systems is sometimes used interchangeably with "local" or "regional" food systems but by including the word "community" there is an emphasis on strengthening existing (or developing new) relationships between all components of the food system. This reflects a prescriptive approach to building a food system, one that holds sustainability – economic, environmental and social – as a long-term goal toward which a community strives. The primer outlines four

aspects that distinguish a community

food system from the globalized food

system: food security, proximity,

self-reliance (sovereignty), and

sustainability.

FDE embodies this type of community food system model by focusing on food security, locality, food sovereignty and sustainability. FDE assists limited resource farmers in meeting living income standards, providing sustainable livelihoods, and moving out of poverty, while ensuring all consumers, regardless of socio-economic background, have access to healthy, affordable food. FDE identified early on that if a regional food system is to alleviate poverty, a specific focus on supporting limited resource farmers in becoming resourceful farmers is paramount. Women and minority owned farms are small, more diverse, and more likely to participate in the local food movement and have been marginalized by the big-agribusiness model. FDE has developed comprehensive strategies that focus on three key elements: an organized and effective system of institutional buying that provides profitable markets for the purchase of local foods; an organized and effective infrastructure to support local and regional food production, including public and private service providers, educational institutions, consumer groups both inside and outside the agriculture sector; and an organized and effective system of nonfinancial/financial support for farmers, to enter or transition to local food production. Building communities in hard times requires innovative strategies and alternative models that ensure the beneficiaries of the system’s development and programs are those who have been marginalized from existing practices. Footnotes

(1) Quote attributed

to Zebulon Vance, North Carolina's

37th and 43rd governor in reference to

North Carolina situated between

Virginia and South Carolina.

(2) See www.feastdowneast.org (3) The FDE Food Sovereignty Program is funded by FMPP USDA grant. (4) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Electronics Benefits Transfer (EBT). Literature

Cited

American Community Survey 2009-2013 Poverty Data: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37000.html Coleman-Jensen, Alisha, Christian Gregory and Anita Singh. 2014. "Household Food Security in the United States in 2013." United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Food Assistance & Nutrition Research Program. Coleman-Jensen, Alisha, Matthew P. Rabbitt, Christian Gregory and Anita Singh. 2015. "Household Food Insecurity in the United States in 2014." United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Food Assistance & Nutrition Research Program. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err194.aspx Cornell University, "A Primer on Community Food Systems: Linking Food, Nutrition and Agriculture," Publisher: Ithaca, New York. 6 pages. Retrieved from: http://www.farmlandinfo.org/ primer-community-food-systems-linking-food-nutrition-and-agriculture DeNavas-Walt, Carmen and Bernadette D. Proctor. 2014. "Income and Poverty in the United States: 2013." Current Population Reports. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. Economic Research Service (ERS), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Food Access Research Atlas. http://www.ers.usda.gov/ data-products/food-access-research-atlas.aspx. Falk, W. W., B. H. Rankin and C. R. Talley. 1993. "Life in the Forgotten South: the Black Belt " in Forgotten Places: Uneven Development in Rural America, edited by L. A. Thomas and F. W. William. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. North Carolina Department of Commerce County Tier Designations: https://www.nccommerce.com/ research-publications/ incentive-reports/county-tier-designations North Carolina Rural Center, Rural Counties Map. Retrieved from: http://www.ncruralcenter.org/rural-county-ma Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. USDA Rural Poverty and Well-Being: Persistence of Poverty: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/ rural-economy-population/ rural-poverty-well-being/geography-of-poverty.aspx

© 2016 Sociation Today

Return to

Home Page to Read More Articles Sociation Today is optimized

for the Firefox Browser

Editorial Board: Editor: George H. Conklin, North Carolina Central University Emeritus Robert Wortham, Associate Editor, North Carolina Central University Board: Rebecca Adams, UNC-Greensboro Bob Davis, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Catherine Harris, Wake Forest University Ella Keller, Fayetteville State University Ken Land, Duke University Steve McNamee, UNC-Wilmington Miles Simpson, North Carolina Central University William Smith, N.C. State University |